Normski: Capturing, Creating, Curating, and Connecting. A Life of Storytelling Without Boundaries

There are few figures that embody the vibrant essence of British and American urban culture through the 80’s, 90’s, and 20’s like Norman Anderson, known to most of us as Normski. The very essence of a creative polymath, his career spans decades and crosses many disciplines—photography, broadcasting, journalism, music, dance, street culture, and fashion—all tied together by his love for capturing, creating, curating, and storytelling. Looking at the breadth of his work, you get the sense that for Normski, storytelling naturally crosses the boundaries of medium or genre, a natural process of capturing the vibrant spectrum of human musical experiences in their most authentic, dynamic, and rhythmically expressive forms.

The Visual Chronicler

Normski's entry into photography is already the stuff of legend. With a sharp eye and a borrowed camera, he began documenting the vibrant street culture of London in the 1980s, immersing himself in the energy of a rapidly evolving social scene.

What’s remarkable, though, is that his journey into photography began almost by accident. As a young boy growing up in Primrose Hill, Normski’s creative spark was ignited when his mother bought him a Kodak Instamatic camera. He had been hoping for a bike, but the small camera, despite its humble origins, became the key to unlocking his fascination with capturing the world around him.

In its toy-like blue and yellow packaging, the camera felt uninspiring at first. Yet, as Normski began experimenting, peering through its lens at the world, something clicked. Influenced by the likes of David Bailey, whose iconic fashion photography set the bar, and inspired by magazines like Photo, he became captivated by the technical and creative possibilities of the medium. He started out with a single roll of film that his mother warned him to use it carefully and quickly learned the value of patience, observation, and the thrill of developing those early images.

By the age of 13, Normski was a hobbyist photographer, earning money to buy better equipment and attending workshops at the Beehive Photography Centre. It was there, in the darkroom, that his passion truly took shape. Watching a photograph emerge on paper for the first time felt like pure magic, a moment that solidified his connection to the art form. A mentor at the centre once told him, “Your vision is your vision. I’m not going to tell you what to photograph, but I’ll teach you how to bring it to life.” Normski’s takeaway was: expensive equipment alone wouldn’t make him a better photographer. What was going to matter far more was mastering the technical elements, understanding how to frame a picture, and, most importantly, cultivating a unique perspective that could capture any moment from any angle. That ethos stayed with him, guiding his instinct to capture moments with honesty and vibrancy.

Normski’s self-taught approach was a process of trial and error. He put himself through an apprenticeship of sorts, taking his camera into the world and photographing anything and everything that caught his eye in his neighbourhood. Through sheer curiosity and immersion, he built a deep understanding of cameras, lenses, and the art of perspective. His photographs from this era are dynamic, living records of a moment in time when hip-hop, dance, and urban fashion were carving out their identity in London.

Through his lens, and over time, the underground world was immortalised with raw honesty and a vibrancy that few could replicate. Photography, for Normski, became a way of documenting culture as it unfolded - preserving the textures, imperfections, and energy of a scene that was alive, electric, and constantly evolving. His journey, totally grounded in passion and driven by an insatiable curiosity, is pure testament to the power of following your vision and taking the time to slow down and really pay attention to the hidden magic in the everyday.

Demon Boyz, Broadwater Farm Estate, London, 1989

Photo credit - Normski

Bboys busking, Covent Garden, London, 1983

Photo credit - Normski

Reflecting on analogue photography, Normski shared an important insight about his craft—he captures the physicality and vitality of the moment. “I look at my black-and-white negatives, or even my colour slides, and there’s this visceral response, it’s like I can feel the moment all over again,” he shared during our conversation. “When I look at certain digital pictures, even the good ones, something’s missing. It’s not the same. It doesn’t feel alive.”

This sentiment ties directly to his lifelong commitment to tangibility, something that has become increasingly rare in a world dominated by pixels and screens. From speaking to Normski, it becomes obvious that analogue photography is much, much more than a technical process, it’s a physical, emotional, and very human experience. “There’s something magical about film—the grains, the texture, the imperfections. It’s like oil paint on a canvas, full of depth and layers that digital just can’t replicate.”

He expanded on the physicality of working with film, from loading rolls to the suspense of waiting for the developed prints in his darkroom at home. “With digital, it’s instant, sure, but with film, there’s anticipation. You don’t just press a button and move on—you think, you frame, you wait. And when you see the final image, it’s not just a photo; it’s a piece of your heart.”

Normski’s views perfectly resonate with The Art of Slowdown’s ethos,‘physical is the new digital’. “We’re so quick to consume, scroll, and discard. But with analogue, you can’t rush it. You must be present, like, really present, in the moment. That’s why it means so much more.”

“The difference between Normski’s photograph of me and any other is that it captures my soul.”

— Goldie

Goldie, Metalheadz, Blue Note, London, 1996

Photo credit - Normski

Analogue vs. Digital & The Search for Soul

Normski believes the lack of soul in digital media stems from its binary, “almost square” nature, “Analogue is organic. It’s fluid. It has contours. There are no straight lines in nature, and that’s what makes analogue special - it connects to something primal in us. Digital, on the other hand, is boxed in, rigid. It gives you everything, but somehow leaves you feeling empty.”

Youth Against Apartheid event, Camden Town Hall, London, 1985

Photo credit - Normski

He contrasted the emotional depth of analogue photography with digital’s technical precision: “Digital can show you every detail, but it lacks the soul. It’s like listening to a song with no reverb or decay—there’s no emotion between the notes. But when you hold a piece of film in your hand or listen to vinyl, you can feel the story, the struggle, the life behind it. That’s what art is meant to do - it’s meant to connect. I think Normski's art reveals that the imperfections and textures of analogue, whether in photography, music, or even life, are what make it real, beautiful, and emotionally compelling. The human mind is deeply attuned to these qualities, which explains why art is so subjective and cherished. Normski expands, “We instinctively seek beauty and crave originality in perspective.. “We’ve got to reconnect with the real, with the things we can touch, feel, and experience,” he said. “That’s where the magic is. That’s where life is.”

In a recent collaboration with the Museum of Youth Culture, Normski launched a limited-edition Zine called, “Darker Shades of White” exploring some of his early artwork documenting street culture in the early 80’s. Normski explained to me that the name comes from the fundamentals of photography, “it’s the physical process of photography itself, where light interacts with a photosensitive surface to create the image that we see”. This duality of "white" (light) and "dark" (the film or negative) is a profound metaphor for creation, contrast, and perception.

Readers are urged to go pickup a copy from the fabulous MOYC while they are still available!

MC Duke, Hanway Street, London, 1988

Photo credit - Normski

The Music Architect

Normski’s unshakeable passion for music began in his early years, playing instruments like the trombone, percussion, bass and drums during his school days. By age 13, he was performing with a band, further honing his musical skills. His first job at the London Rock Shop in Chalk Farm immersed him in the world of drum machines, synthesizers, and other musical equipment, laying a solid foundation for his future endeavours in the music industry.

Transitioning into the role of a DJ, Normski became a prominent figure in London’s club scene, known for his eclectic sets that seamlessly blended genres and eras. His deep understanding of music’s emotional narrative allowed him to curate experiences that resonated with diverse audiences. Beyond live performances, he made significant contributions to radio, appearing on stations like BBC Radio 1, Kiss 100, Push FM, and Flex FM, where his shows became a nexus for music enthusiasts seeking innovative and authentic sounds. In-fact, as I write this piece Normski has just graced the decks at Fabric, one of the most famous electronic landmarks in London, (perhaps the world).

By the mid-1980s, Normski’s lens had become a gateway into the world of hip-hop, documenting the explosive emergence of rap and dance music as it took centre stage in popular culture. His unshakeable passion for music, combined with his keen understanding of perspective and the fundamentals of photography, merged into a unique vision. This synthesis enabled him to capture the energy and essence of the culture in a way that others struggled to achieve.

Ice Cube, Inglewood, Los Angeles, 1992.

Photo credit - Normski

In 2003, he staged the ‘Hip Odyssey’ collection, a 60-piece retrospective of his street and rap photography from the 90s. His work was published in The Face, Vogue, Hip-Hop Connection, Ministry, NME, and i-D, capturing the raw dynamism of British artists such as Goldie, Stereo MC’s, and Soul II Soul, and American icons of the time like De La Soul, Public Enemy, Ice Cube, N.W.A., Afrika Bambaataa, and Wu-Tang Clan.

It’s not hyperbole to say that his images have become cultural artifacts, revered not only for their vibrant aesthetic but for the historical context and vast record they provide of a period of great artistic innovation.

De La Soul, Brixton Academy, London, 1989

Photo credit - Normski

“He was a larger-than-life character, full of energy and totally motivating. He really was the hip hop photographer of the day in the UK.”

— Stereo MC’s

Fashion and Cultural Influence

Normski's influence on fashion is strongly connected to his engagement with the hip-hop scene during the 1980s and 1990s. As a curator, he utilised his unique styling skills for the Hip-Hop B-boy section in the "Street Style from Broad Walk to Catwalk" exhibition at The Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in the early 90s, which showcased street style fashion from the 1950s to the 1990s. Additionally, he contributed a collection of Hip Hop fashion items and photographs that are now part of the museum's permanent archive. The demand for his photography has led to its use in various T-shirt designs, with more projects planned for 2025.

In the early 90s, as a TV presenter on the groundbreaking music and culture show "Dance Energy," he consistently set style trends across the nation. He traveled both domestically and internationally to discover individuals and showcase their street styles to the masses through the ever-popular "Style Squad" fashion police feature on BBC 2's influential Def II programming slot.

Through his multifaceted contributions to music and fashion, Normski has solidified his status as a cultural icon, continually shaping and reflecting the artistic zeitgeist of his time.

Cookie Crew backstage at Camden Town Hall.

Photo credit - Normski

Curating, Creating, Capturing, and Connecting

If there’s one word that defines Normski’s career, it’s got to be "connector." He naturally bridges worlds that are too often seen as disparate: photography and music, underground and mainstream, art and commerce. His career isn’t a sequence of isolated roles, and perhaps without even being consciously aware of it, reads as a cohesive whole, with each chapter very naturally connecting to and informing the next; and always about passion for people, community and storytelling.

I think his philosophy can be summed up by a guiding principle: "Don’t limit yourself to one dimension of creativity when you can live in many." This approach has made him a trusted name across industries. He’s been called upon to photograph cultural icons, DJ at exclusive events, and appear on television as both subject and host. Each project is part of a larger mosaic, not just of his career, but of cultural storytelling itself.

Normski is also an ambassador for the Museum of Youth Culture, a brilliant organisation dedicated to preserving and celebrating over a century of teenage life in Britain. With his roots in London’s vibrant 1980s scene, he brings a unique perspective to the role, helping to highlight the creativity and cultural significance of youth. His involvement is also part of continuing theme - and heartfelt commitment - to preserving the stories that shaped Britain’s identity, ensuring the energy and impact of youth culture are recognised and remembered.

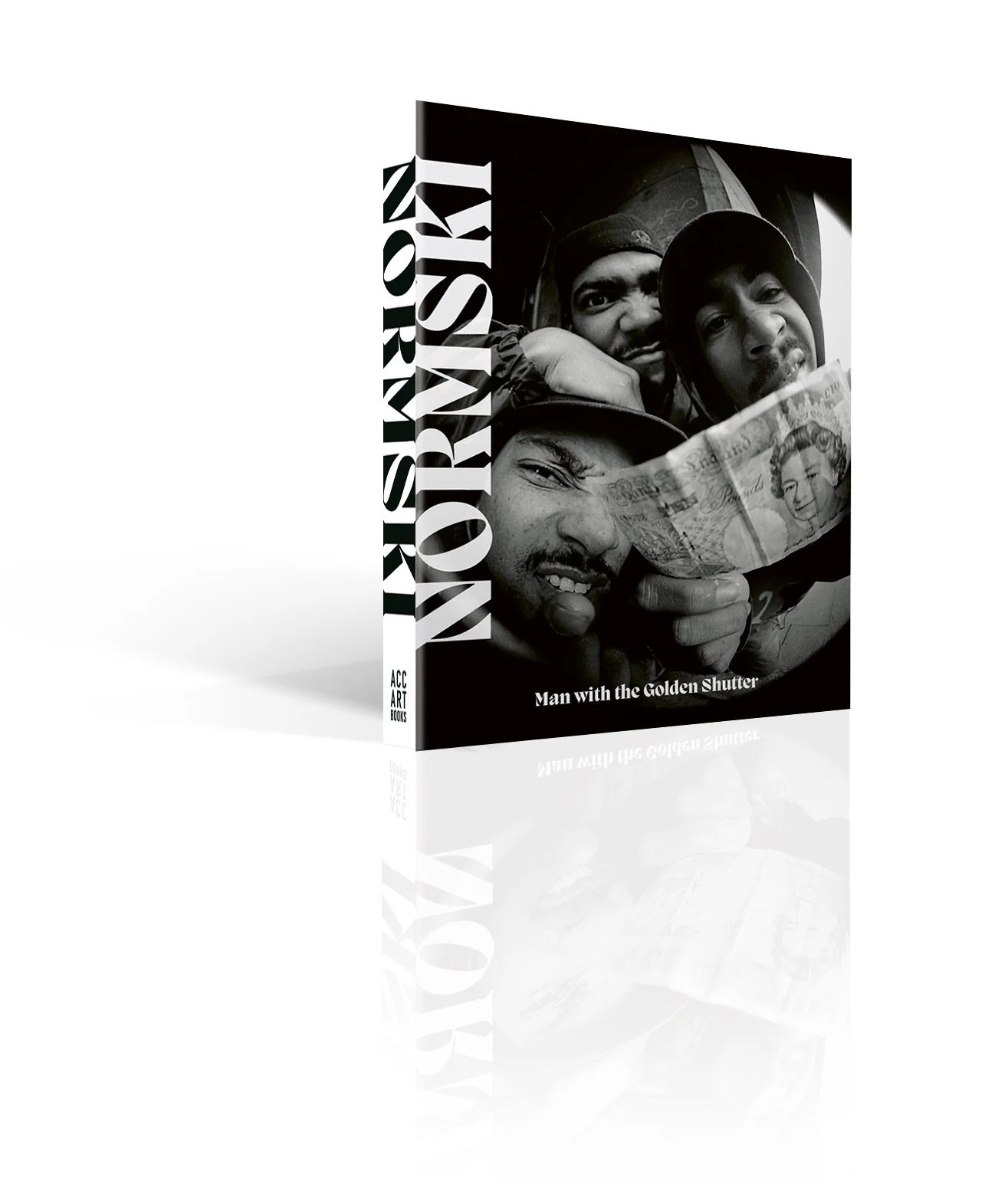

The Man With The Golden Shutter

Normski recently released his landmark book, The Man with the Golden Shutter, offering a vivid and personal window into his career during the pivotal years of hip-hop and street culture. Published by ACC Art Books, a leader in the arts, the book spans the mid-1980s to early 1990s—a period often called the Golden Age of Rap. It captures the energy of an era shaped by the rise of American hip-hop legends like Run DMC, Public Enemy, and N.W.A., alongside the birth of distinct British sounds such as Jungle, Garage, and Techno.

Featuring over 200 photographs, many shared with the public for the first time, the book showcases not only iconic artists but also the raw, everyday vibrancy of the UK's hip-hop scene. What sets The Man with the Golden Shutter apart is the way Normski weaves personal stories into each image. These personal anecdotes add his thoughts, and so, much more depth to the striking visuals, offering readers a real sense of the people and moments behind the lens. Normski's unique perspective is evident throughout, as is his deep engagement with his subjects, brining an authenticity and purpose to every moment he captures, making the book as insightful as it is dynamic.

“This book contains a striking catalogue of images, many of which have been exhibited by establishments such as Tate Britain, the V&A, Somerset House and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.”

— Marcus Barnes

I’m delighted to say that book has been widely praised for its role in preserving the history of British hip-hop and street culture. Critics have highlighted how it shines a light on both the iconic and lesser-known figures who shaped the scene, offering an authentic and original look at one of the most influential cultural movements of its time. The Man with the Golden Shutter is already regarded as essential reading for anyone passionate about hip-hop culture and photography, celebrated for capturing the evolution of the genre through Normski’s unique lens. Reviews have noted its dual importance as both a historical record and a deeply personal narrative, securing its place as a defining work in the study of music, culture, and art.

If you haven’t already, my advice is simple—buy a copy. It’s a stunning piece of work, a true objet d’art that elevates the culture and the people it so vividly portrays.

Chuck D & Flava Flav Def Jam 87 Hammersmith Odeon 1987.

Photo credit - Normski

Reflecting on Normski's Approach and the Art of Slowdown

Normski’s journey perfectly captures the balance of pace and purpose, a duality that often sits at the heart of true creativity. While his career has naturally evolved across many creative disciplines, I believe that it’s his ability to fully immerse himself in each moment that allows his art to transcend time, convey his vision and passion, and capture its very essence, no matter the medium. When we’re fully immersed in our art, a photograph is elevated to much more than a mere snapshot; it’s a communion with the subject. A DJ set isn’t simply music; it’s a carefully curated listening experience that is tailored to, and deeply connected with the audience. Curated and enhancing the emotional impact of the moment. Each creative act is reflective an ethos of physical presence and intentional engagement, an absolute cornerstone of ‘The Art of Slowdown.

Normski reminds us that slowing down doesn’t diminish the quality of our actions or drain our energy; instead, it allows us to sharpen our focus and enhances our intentionality. In a world where speed is too often equated with productivity and celebrated as the ultimate goal, Normski’s approach offers a refreshing perspective.

His method involves a deliberate pause, a moment of observation, followed by action that is both incredibly precise and purposeful. His creative process underscores a natural instinct to engage deeply with - and get right up and close to - his surroundings, the people, and the varied subjects of the moment. A quality that seems increasingly scarce in our fast-paced, overstimulated culture. Embracing a slower, more considered rhythm, Normski enriches his creative output and offers us a glimpse into his unique perspective, urging us to reflect on our own pace in life. He may be fast and energetic on the outside, but my feeling is that on the inside, Normski is deep, contemplative, and highly aware, living attuned to the noise and kinetic energy all around him. Perhaps this is how he emotes so freely and naturally with anyone he meets, his inner depth allowing for a genuine connection.

Queen Latifah, Empire State Building, New York City, 1980s

Photo credit - Normski

Normski is a larger-than-life authority and influence on British music and youth culture. Through his unique ability to galvanize, curate, and capture the vivid and vibrant essence of these movements, he has become a cultural force. From behind the camera to behind the scenes, Normski’s presence has left an indelible mark on the story of British creativity, bridging past, present, and future with every frame, beat, and word.

As we all navigate a world that too often prioritises speed over substance, Normski’s career challenges us all to rethink our relationship with time. To slow down is not to halt progress but to align with the rhythm of what really matters; a deeply personal journey for each of us.

NORMSKI NAME BELT "I got this in NYC in 1986 and This was the birth of my knickname"

Photo credit - Normski

His life work is a testament to the power of thoughtful creation, and of deliberate storytelling, always compelling us to listen, to see, and to feel with greater clarity. His sometimes quiet, and often loud and vibrant reflections inspire a universal call to action, "to get out there and tell your story, create your own narrative." From spending time listening to Normski’s own journey, my advice is to just start; you'll improve, and you'll feel a whole lot better about it. Only by following our own stories, allowing ourselves to swim in the river of our own vision, can we uncover the magic hidden in the everyday and amplify the stories that define who we are…

A heartfelt thank you to Normski for collaborating with us on this piece and giving us the opportunity to share just a glimpse of his remarkable career and life journey. We know this is only the beginning, and we can’t wait to see what incredible chapters lie ahead.

Andy Oattes

You can pick-up a copy of “The Man with the Golden Shutter” in all great bookshops and we urge you to do so. Get your own signed copy from online shop over at Museum of Youth Culture

All images © Norman Anderson / Normski